Some of the stories represented in this week’s batch of pictures are truly captivating. Whether it’s bearing witness to the gruesome but ecologically essential process of parasitism, reveling in the complexities of biological pest control, or simply knowing that a butterfly you see right now could survive the harsh Montana winter and emerge to greet you early next spring, insect lives are endlessly surprising and fascinating. What wonders are you beholding?

Submit your bug pictures to bugid@missoulabutterflyhouse.org (and remember to include your name, the date, and the location where you took the photo)!

Header photo: The reddish-brown bands on its wings make the Band-winged Meadowhawk (Sympetrum semicinctum) one of the easiest species of meadowhawk to identify. Preferring shallow ponds, marshes, and bogs with slightly flowing water, its habitat options are more limited than other dragonfly species because the nymphs apparently do not compete well with other dragonfly species and are highly vulnerable to fish predation. Found throughout the United States and southern Canada, this species is most common in late summer and remains on the wing into October. – Connie Geiger, August 24, 2025, Helena, MT

Crimson-ringed Whiteface

Leucorrhinia glacialis

This beautiful dragonfly typically emerges in June and can be found in marshes and boggy areas across the northern half of the United States and into Canada. It is on the wing into August and can often be spotted perching on the ground where it waits for passing prey before launching a feeding attack. On hot days you may even see one in a handstand-like position (obelisking) to control its temperature. Although its global population is considered stable and it can be locally abundant, the Crimson-ringed Whiteface is considered a Potential Species of Concern in Montana.

Glenn Marangelo, August 14, 2025, near Condon, MT

Pacific Fritillary

Boloria epithore

Favoring moist meadows in woodland and forest openings, this butterfly is mostly found in mountainous areas of the Pacific Northwest and California. Larvae feed on violets (Viola spp.), while adults feed on nectar from a variety of flowers. This species can be distinguished by the dark “chevron” marks along the submargins of each wing – in B. epithore, these chevrons point outward, while in other lesser fritillaries (genus Boloria), the marks point inward.

Glenn Marangelo, August 15, 2025, Jewel Basin, near Bigfork, MT

Vashti Sphinx Moth with parasites

Sphinx vashti

When Dalit first observed this Vashti Sphinx caterpillar, it was munching away on a patch of snowberry (Symphoricarpos spp.), it’s preferred food source. Over the subsequent days, however, she watched as the caterpillar became a preferred food source itself – to dozens of parasitoid wasp larvae. Most likely a type of braconid wasp (family Braconidae), the female wasp would have used her ovipositor to lay the eggs on or under the caterpillar’s skin. Once the eggs hatch, the wasp larvae feed on the caterpillar’s viscera, then chew through the skin before they spin a cocoon and pupate, still attached to the caterpillar. The white “growths” visible in the photo are actually wasp cocoons; look closely, and you can even see new holes where the wasp larvae are emerging. Braconid wasps are such effective parasites – females can reportedly lay up to 200 eggs a day – that they are used as biological control for soft-bodied garden pests.

Dalit Guscio, August 23, 2025, Missoula, MT

Four-spotted Moth

Tyta luctuosa

Introduced to western North America in the 1980s as a biocontrol for invasive Field Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis), this moth is native to central Asia, northern Africa, and central and southern Europe. There are typically two generations per year, with the first adults emerging in late spring, and the second in late summer. Females can lay 400 to 500 eggs, and the drab brown larvae feed on bindweed flowers and leaves before pupating. Larvae and adults both overwinter in plant litter.

Klara Briknarova, August 23, 2025, Missoula, MT

Sharptail Bee

Coelioxys sp.

Coelioxys – pronounced seal-ee-OX-ees – is Ancient Greek for “sharp belly.” Also called cuckoo leafcutter bees, sharptail bees belong to the same family (Megachilidae) as the leafcutter bees they parasitize. Considered cleptoparasites, females do what cuckoos do best: they let someone else provision their young. According to The Bees In Your Backyard, “Coelioxys use their pointy abdomen to break a hole into closed leafy nest cell walls of their hosts. They lay an egg inside, and when it hatches (which is almost immediately), it uses tweezer-sharp mandibles to snip the egg or young larva of the host bee in half.” The Coelioxys larva is then free to consume the stored pollen originally collected for its host. Because they do not need to collect pollen for their own offspring, sharptail bees lack the pollen-collecting scopa on the underside of their abdomen, but otherwise superficially resemble leafcutter bees.

Connie Geiger, August 24, 2025, Prickly Pear Creek near Helena, MT

Potter Wasp

Eumenes sp.

Potter wasps are solitary wasps belonging to the subfamily Eumeninae. Their common name derives from their unique nest-making technique, where females construct small, urn-shaped nests from mud and regurgitated water attached to twigs. An egg is laid into each nest, and the larva is provisioned with a paralyzed caterpillar for food. Some North American Indigenous peoples may have taken inspiration from the nest shapes of local potter wasps for their own pottery designs. There are eight species of Eumenes in the United States and southern Canada, and more than 100 species worldwide. Although capable of stinging, these wasps are rarely aggressive.

Misty Nelson, August 24, 2025, Missoula, MT

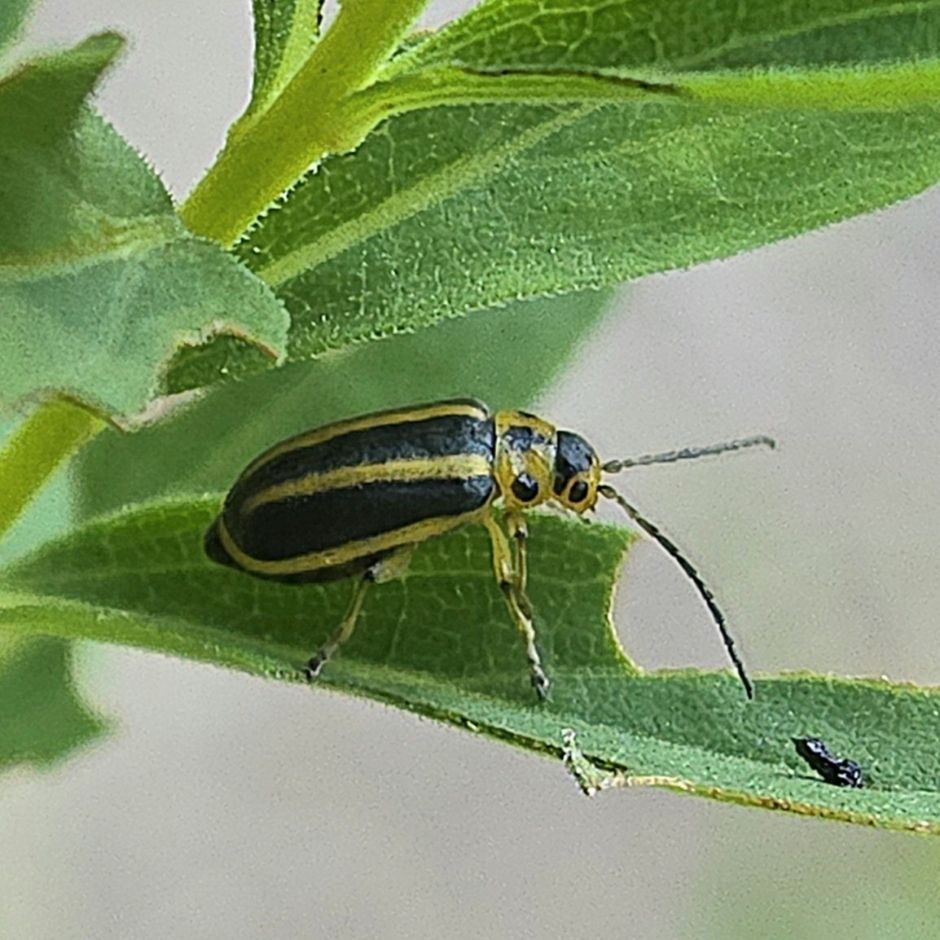

Leaf Beetle

Trirhabda sp.

Leaf beetles in the genus Trirhabda can be difficult to identify to species, but all have some common features. You will notice that the top side of the thorax is yellow with three round or oblong spots and the rear top of the yellow head also has a dark spot. Many, like this one, have longitudinal stripes on the wing covers. Adults and larvae are plant-eaters and feed on leaves and flowers of a single plant species or genus in the aster (Asteraceae) or waterleaf (Hydrophyllaceae) families; the host plant is often a key to identifying species. These beetles are found in weedy fields and brushy areas and range across North America from southern Canada to Central America. As an interesting aside, “pregnant” or gravid females have remarkably distended abdomens – check out an example here.

Judy Halm, August 24, 2025, Helena, MT

Tobacco Budworm Moth

Chloridea virescens

Caterpillars of the Tobacco Budworm Moth vary in color from green to yellow to maroon, seemingly taking on the color of what they are eating – in this case, bright pink snapdragon flowers. Widespread throughout South and Central America and the southern U.S., this species disperses northward as far as southern Canada. It has also been introduced in the Pacific Northwest via larvae inadvertently imported on cultivated nursery plants. Larvae feed on a variety of host plants, and it is considered a major agricultural pest, particularly for cotton and tobacco (hence its common name).

Qin Yu, August 27, 2025, Missoula, MT

Knapweed Root Weevil

Cyphocleonus achates

This non-native weevil was introduced to western North America in the 1980s to help combat another exotic – invasive Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe). Females lay their eggs on the top of the knapweed’s root crown. Once they hatch, the larvae burrow into the plant’s root, destroying the vascular root tissue and preventing it from transporting water and nutrients. Death of the plant can occur within two years. Research at Montana State University has shown up to a 99% reduction in knapweed density due to the introduction of Knapweed Root Weevil. Go weevils!

Jamie and Josh Demers, August 27, 2025, Missoula, MT

Satyr Comma

Polygonia satyrus

Commas, so named for the white “comma” on the cryptically-patterned underside of their wings, can be some of the trickiest butterflies to identify. Luckily, the species the Satyr Comma is most often confused for, the Eastern Comma (Polygonia comma), is not found in Montana. Commas are hardy, long-lived butterflies. They mature in late summer and early autumn and overwinter in their adult stage. They emerge in the spring to mate and lay eggs; because of their long lifespan, adults can be seen year-round (but are less common in late spring and early summer).

Kelly Dix, August 21, 2025, Cabinet Mountains, MT