Welcome back to the Lab!

Since 2015, our colony of walking sticks, Medauroidea extradentata, have been reproducing via parthenogenesis (cloning), resulting in an all-female colony of clones. This method of reproduction is so successful that males are practically non-existent; absent from captive collections and extremely rare in the wild. At least, that’s been our messaging surrounding the species.

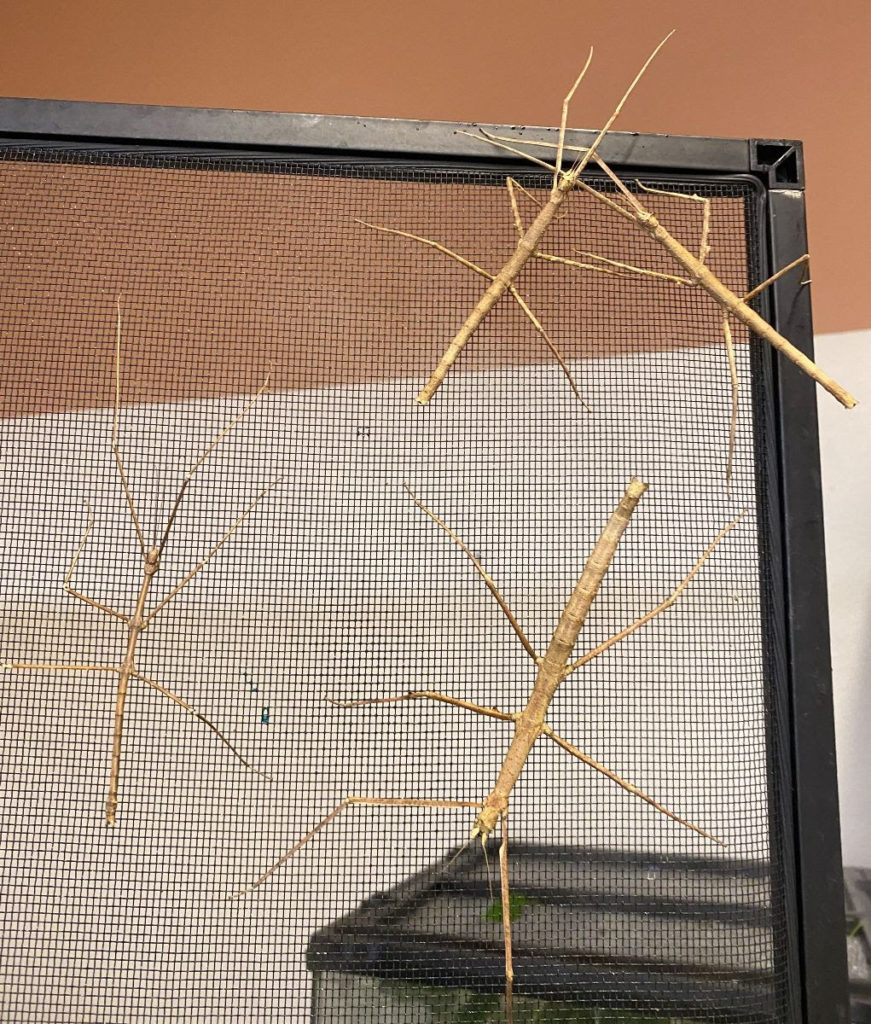

Until several weeks ago, when I noticed a walking stick in our colony that just seemed… off. The presence of reproductive organs told me the individual was an adult, but it was more slender and leggier than the rest of the colony. When you’ve spent every day for the last five years with a particular animal, the smallest differences become obvious, and my brain was telling me this was undoubtedly a male. Yet I stared at the insect for a solid 15 minutes in disbelief before posing my question to the internet. How did this happen?

While the appearance of a male in a parthenogenic colony of insects is certainly rare, it’s not unheard of. In 2018, a male stick insect belonging to the genus Acanthoxyla – a group of stick insects that only reproduce via parthenogenesis – was found in the countryside of Cornwall, England; the first of its kind. The mechanism behind the phenomenon of “rare males” varies between species, but in any case, it all comes down to chromosomes.

Sex determination is not universal across all species. In humans, sex is determined by XX/XY chromosomes. In an XY sex-determination system, eggs carry an X chromosome, and sperm carry an X or a Y, which in turn determines the sex of their offspring (XX for females and XY for males).

In stick insects (as well as many arachnids, nematodes, cockroaches, grasshoppers… the list goes on) sex is determined by XX/X0 chromosomes; in these species, eggs carry an X chromosome, while sperm carries an X chromosome or no chromosome at all. In an X0 sex-determination system, females have two sex chromosomes (XX) and males only have one (X0).

In the case of our male stick insect – and many “rare males” in parthenogenic populations – he is probably the result of a lost chromosome. A mere chance event that led to something none of us at MBHI have ever seen. The question remains whether or not he is capable of reproducing; and if he is, it opens the door to a whole new line of inquiry.

Until next time, thanks for visiting the lab!

Bug Wrangler Brenna

brenna@missoulabutterflyhouse.org

Want to revisit a previous Notes from the Lab issue? Check out our archive! Do you want to request a subject for an upcoming issue? Email me at the address above and put “Notes from the Lab” in the subject line.