It’s no secret that certain insects have long been associated with death and decay. Flies and their offspring, carrion beetles; they are the masters of decomposition, responsible for the rather foul job of nutrient cycling so that organic material can be reused by the ecosystem. It’s a dirty job, but without them, we’d be swimming in filth.

Additionally, forensic scientists would be left without a key component of crime scene investigation. By exploiting the natural behaviors of nature’s decomposition specialists, scientists can uncover crucial truths about a person’s demise. This lucrative field of forensic investigation is known as forensic entomology.

Disclaimer: While this article will not contain any graphic photos, discussions of death and decay will follow, so take care if you’re the squeamish type.

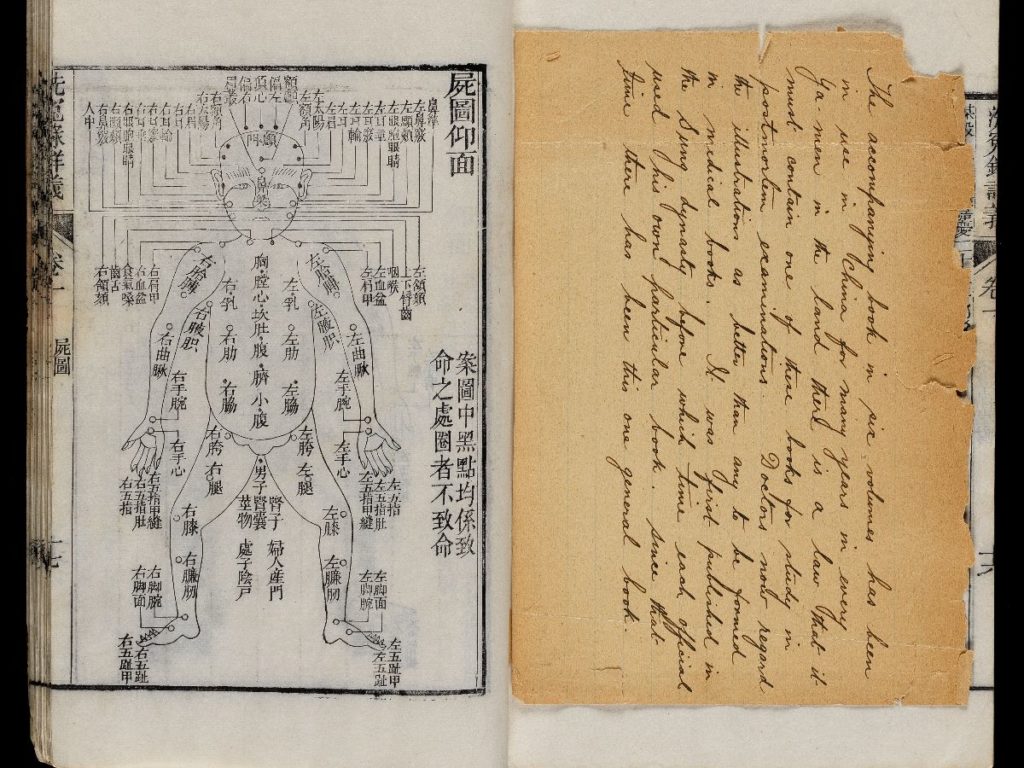

Forensic entomology has a long history, with the first evidence of insects being used in a forensic investigation in 13th-century China. Sung Tz’u, a Chinese lawyer largely credited with being China’s founding father of forensic science and the world’s first forensic entomologist, recounts using insects as a means for forensic investigation in his 1247 text Washing Away of Wrongs (or Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified). In the text, Sung Tz’u describes a case where a corpse exhibiting multiple slashing wounds was found in a rice field. Suspecting the murder weapon to be a sickle (a common tool used for harvest), local officials rounded up the area’s farmers and ordered them to place their tools on the ground. Though every sickle appeared clean to the naked eye, blow flies were quickly drawn to the tool used in the gruesome crime, attracted by the scent of trace amounts of blood and tissue left on the weapon. The owner of the sickle confessed shortly thereafter.

Sung Tz’u’s text on forensic investigation predates European texts on the subject by hundreds of years, and it wasn’t until the 1800s that forensic entomology emerged again in the historical record. In 1855, French physician Bergeret d’Arbois used insects to establish an accurate time of death based on the succession of insect colonizers to a corpse. By using his knowledge of insect life cycles, d’Arbois successfully argued in court that a corpse discovered behind a wall had been placed there years earlier, exonerating the building tenets of the crime.

D’Arbois’ methods of forensic analysis are still used in forensic entomology today. By determining the amount of time it takes for specific species to colonize a corpse, and the development rate of their offspring, forensic investigators can establish the time between death and corpse discovery, known as the post-mortem index (PMI).

For example, in the first few minutes following death, cellular breakdown occurs. While this does not result in any immediate physical changes, insects can still detect the chemical byproducts of cellular breakdown and are attracted to the corpse or carrion. Blow flies and flesh flies are usually the first to arrive. As the body decays in the following days, other insect species continue to colonize the corpse; by day four, Dipteran (flies) larval stages are present. You might know them as maggots.

By identifying the species present and the timing of their life stages, forensic scientists are able to determine a post-mortem index with relative accuracy. Insects can also give investigators information on whether or not the body was moved and if any toxins were involved, as insects will accumulate any drugs present as they feed. While we may associate them with filth and decay, the insects responsible for decomposition help investigators tell a story of how a person or animal died. They’ve become an integral part of forensic investigation; you just have to know how to read them.