Welcome back to the Lab!

What did you have for breakfast this morning? Cereal? Eggo waffles? Pan-fried scorpion? If consuming insects has never crossed your mind, then you’d be considered the minority. Western culture has long shunned the practice, but worldwide, insects are consumed with gusto.

In fact, when it comes to eating insects, North America and Europe are the exceptions to the norm. But it might be time for us to get on board, because eating insects provides a lot of benefits; not only to the individual but potentially as a more sustainable protein source for society at large.

It’s news to no one that animal agriculture takes a toll on our planet, from land use to greenhouse gas emissions. Insect cultivation for human consumption, known adorably as “minilivestock” can cut back on the ecological and economic costs of rearing livestock.

For example, production of 150g of grasshopper meat requires very little water, while cattle requires 870 gallons to produce the same amount of beef.

There is also an option to utilize pest species as a source of food. In Mexico, the grasshopper species Sphenarium purpurascens is a major crop pest, but is harvested by farmers to be used as a food source (known as chapulines, pictured above). Not only does the grasshopper harvest net an additional source of income for these farmers, but it reduces the pest population without the use of pesticides.

If you’ve been involved with the Missoula Butterfly House and Insectarium for a while now, you’re probably familiar with our annual banquet, Bug Appetit; every year we team up with Burns Street Bistro to offer fine insect dining.

While the menu we present every year is more like fine dining with the addition of insects, many cultures around the world utilize insects as the base of the dish rather than a fun addition. If you want to explore the world of entomophagy for yourself, why not start with a tasty mealworm snack, and work your way up from there? Or jump right in and try one of the following more adventurous dishes!

Chocolate Chirp Cookies

For those of you that are still squeamish at the thought of eating bugs, we’ll start out with an insect-based food that might be easier for you to digest: the chocolate ‘chirp’ cookie. Commonly made from dried and ground crickets, this cookie is hardly distinguishable from its classic counterpart (and boasts an impressive serving of protein to boot). Ground cricket flour is often the gateway ingredient into entomophagy; you’ll be on your way to more adventurous eating in no time!

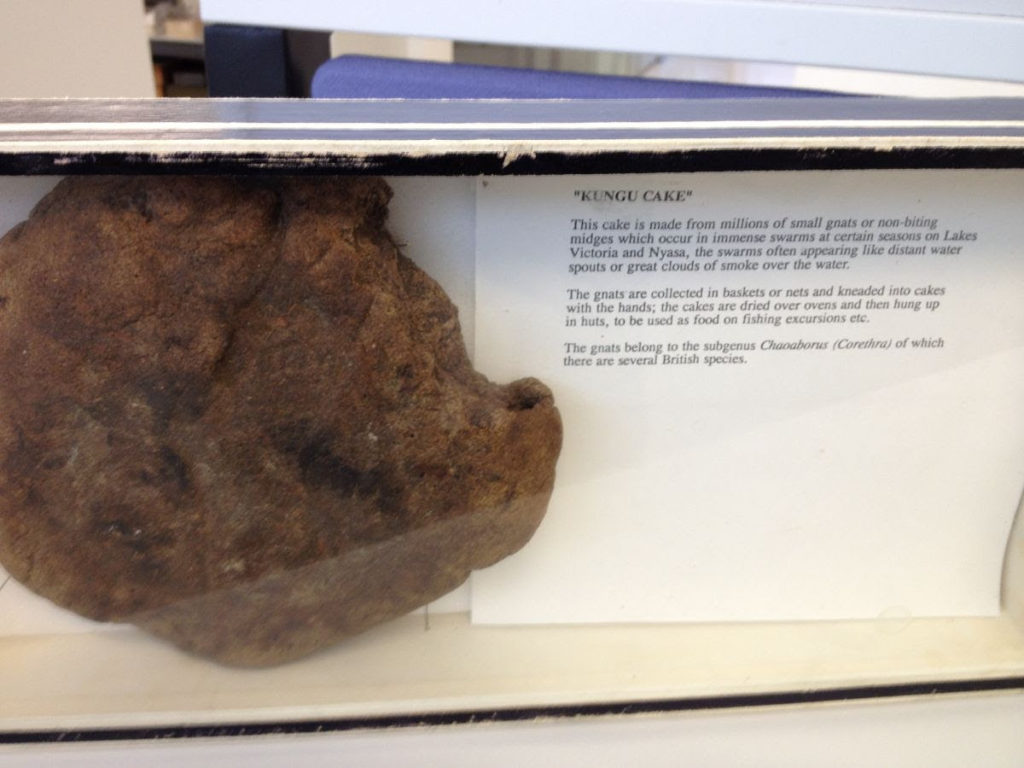

Kunga Cake

Ever ridden your bike through a swarm of gnats and consumed a few in the process? For many cultures, consuming insects can be the solution to significant problem, specifically the challenge of living in areas where insects are hyperabundant and tend to swarm. Enter, the kunga cake; a popular dish in east Africa that is made by compressing millions of midges (small flies) into a cake or patty.

The cakes can be consumed as is, or even grated and used as a seasoning, much like parmesan cheese (they are described as being rich in umami flavor, that ever-desirable flavor you get from MSG). The midges form huge swarms in east Africa, and local populations have an ingenious way of collecting them: just coat a cooking pan in oil, waft the pan through the swarm. Voila. Lemons into lemonade.

Roasted Tarantula

While consuming tarantulas and other arachnids is technically known as arachnophagy, 8-legged delicacies are consumed around the world as much as their 6-legged counterparts. Fried scorpion is common street dish in southeast Asia, but in South America, one indigenous tribe has mastered the ultimate arachnid snack: roasted goliath bird-eating tarantula (Theraphosa blondi).

The Piaroa are native to the Orinoco Basin in Venezuela have long been consuming the largest spider in the world. According to Rick West, a tarantula expert reporting for National Geographic, “The white muscle ‘meat’ tastes like smoky prawns, while the gooey abdominal contents are hard-boiled in a rolled leaf and taste gritty and bitter […] The three-quarter-inch fangs are used after the meal as toothpicks to remove T. blondi exocuticle from between one’s teeth.”

Now, who’s hungry?

Until next time, thanks for visiting the lab!

Bug Wrangler Brenna

brenna@missoulabutterflyhouse.org

Want to revisit a previous Notes from the Lab issue? Check out our archive! Do you want to request a subject for an upcoming issue? Email me at the address above and put “Notes from the Lab” in the subject line.